Mark Simon is a storyboard artist, author, animation director, and entrepreneur who runs Animatics & Storyboards Inc., a storyboarding company with more than 5,000 productions to its credit including The Walking Dead, Dexter, Stranger Things, and The Flight Attendant.

Jump to section:

- What is a storyboard artist?

- How did you get into storyboarding?

- How does one become a storyboard artist?

- Do different storyboard artists have different visual styles?

- How does a storyboard artist fit into the overall production workflow?

- Who does a storyboard artist work with most on-set?

- What is your own, off-set workflow?

- What tools are required to be a storyboard artist?

- Which Wacom products do you use?

- What types of files do you send?

- Does working remotely affect your workflow?

What is a storyboard artist?

Our function is to illustrate the director’s vision of a script. If you think about reading a script, what’s in your mind is different than what’s in anyone else’s mind. And on The Walking Dead, for example, we’ve got between 500 and 700 people on the set every day. That’s a lot of different visions and a lot of potential problems. So we illustrate the director’s vision. They use it for budgeting, scheduling, planning—figuring out what can happen and what can’t happen. And so now the entire crew has a singular vision which saves a tremendous amount of time and hassle.

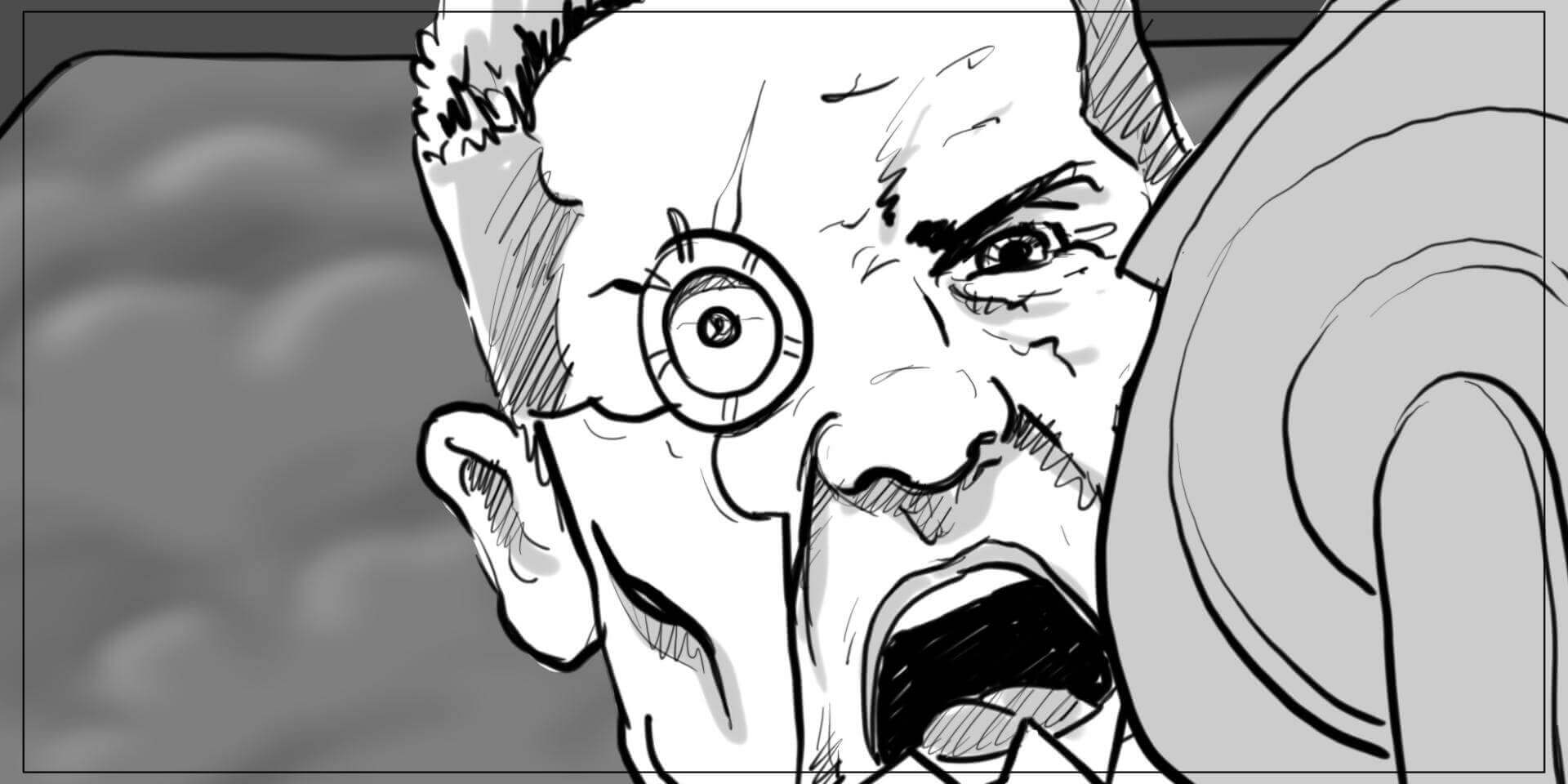

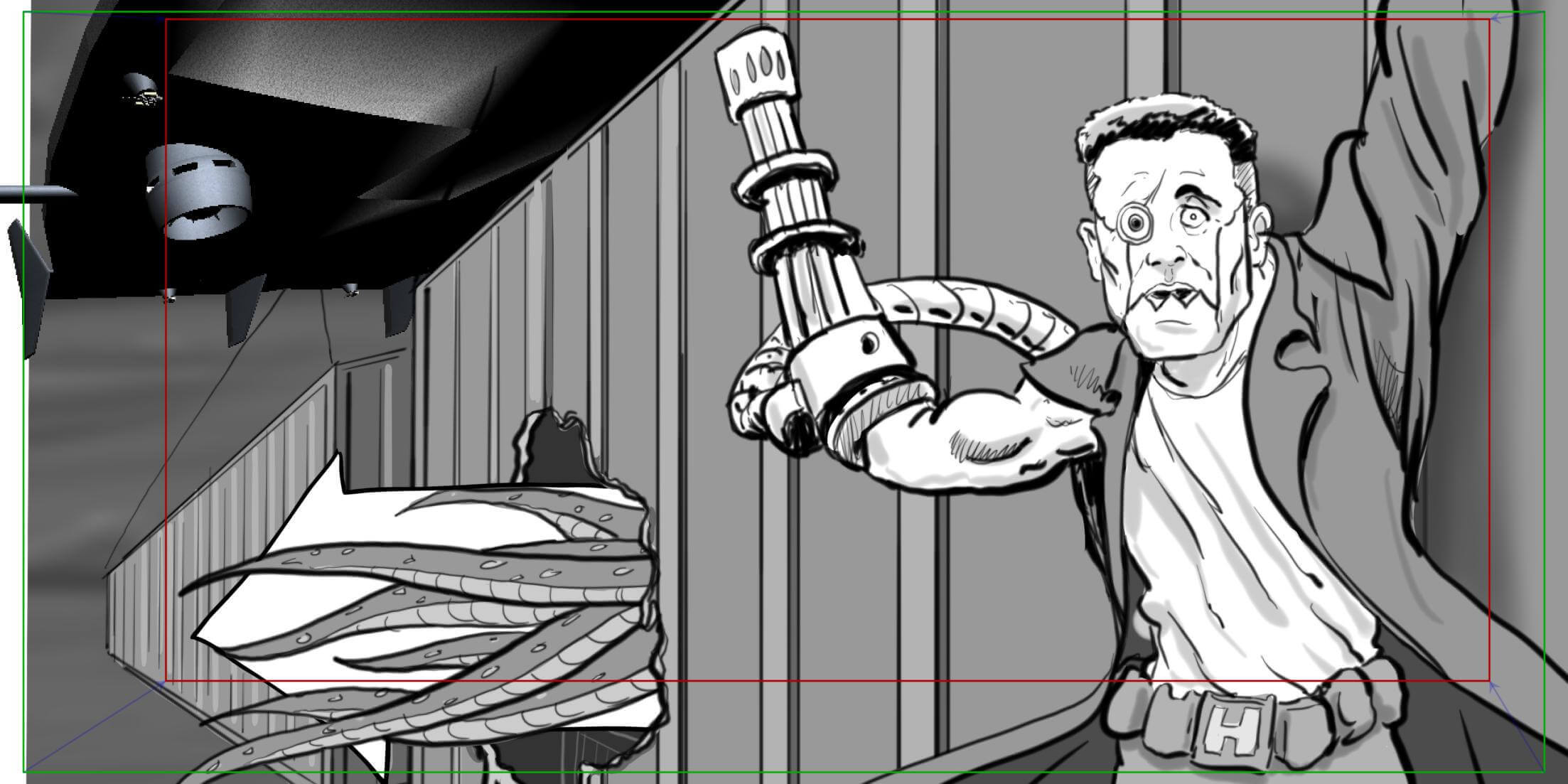

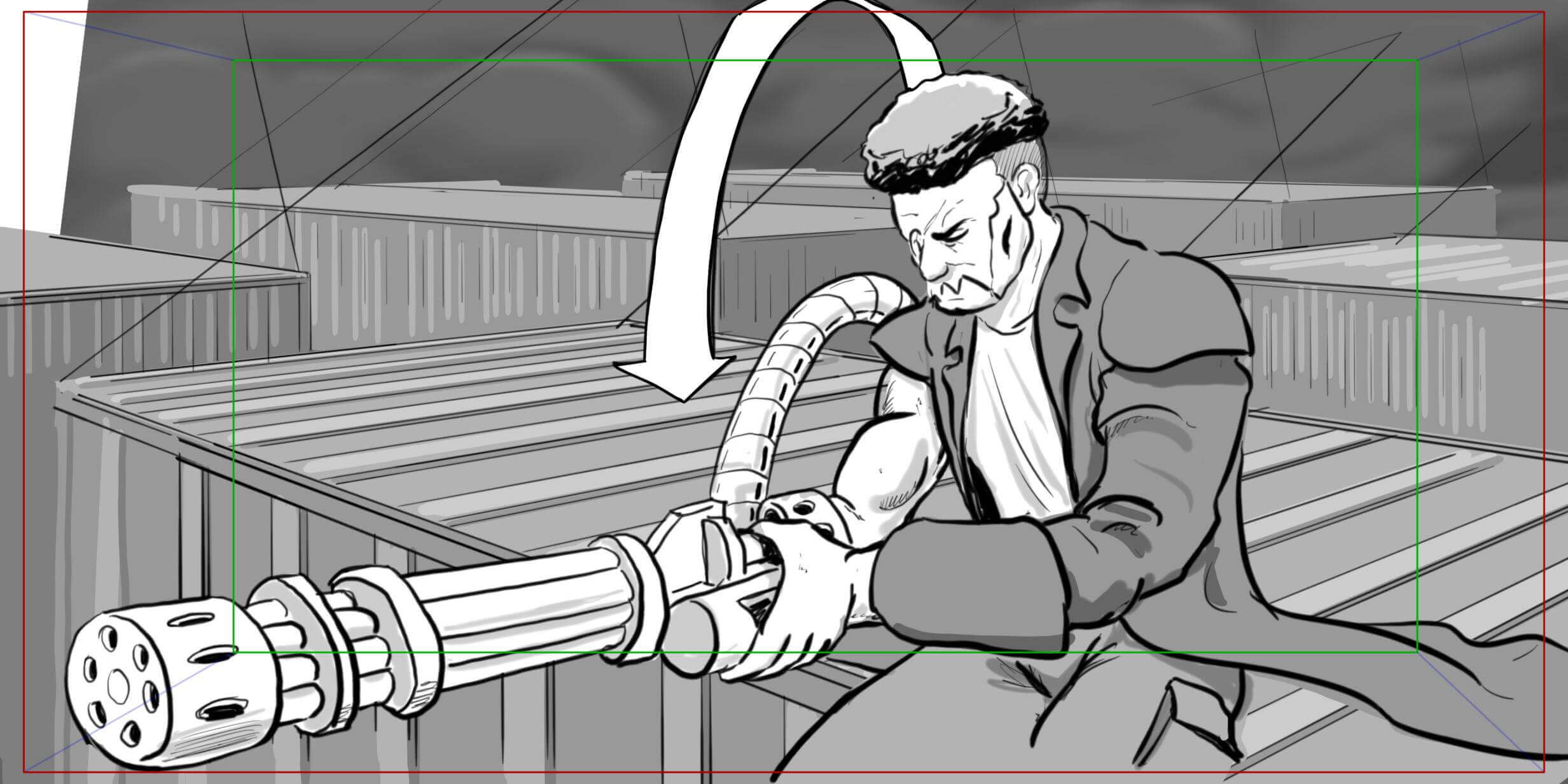

All storyboard frames featured have been provided by Mark Simon

How did you get into storyboarding?

My dad had a homebuilding business, so I started designing his marketing materials, brochure illustrations, and architectural renderings for the company. Eventually, his clients and contractors came to me, so I started doing marketing for them. I launched a marketing company and paid my way through college with it.

After I graduated college I was living in L.A., and I figured art directing in set construction would be my way into Hollywood because I knew how to design and build things. I’d done it my entire life. So I went to Roger Corman’s studio and applied for a job. If anyone doesn’t know Roger Corman, he was the king of the budget movies and half of Hollywood got their start in his studio. I got a job on a science fiction movie called Slave Girls From Beyond infinity as construction coordinator. Two weeks later I was made the art director, because I knew how to run crews.

But I wanted to be more into the storytelling. So I went to the biggest agency in the world, Storyboards Inc. I walked in and asked to meet one of the agents, and showed him my samples. He said it was terrible. I asked a lot of questions. He gave me some samples. I went away. I showed back up a week later. He said, ‘Well, better, still not good.’ So he gave me a couple more tips. I went away again. And I just kept showing up until he finally said ‘Hey, you want a Honda commercial?’ And they started placing it. So during that time I started transitioning into doing more storyboarding.

Now, where construction really came into help is, as a story artist, we have to be able to draw anything quickly. People, cars, animals, anything—and that includes locations in perspective. Having worked in construction, I constantly had to draw things in perspective, based on blueprints. To show my crew. I need to do this, this is how this joint is going to work. So it was second nature by then, because my entire career growing up was sketching things in perspective so everyone can understand it.

And so now when I’m working with directors, and they say ‘All right, I want the 20 millimeter lens 30 feet high looking in this direction,’ I can sketch it up in perfect perspective.

How does one become a storyboard artist?

There are courses now, but not when I came through. I actually wrote the first in-depth book on storyboarding, and the third edition is used in universities around the world to train story artists, and has been published in seven different languages. I’ve personally written three different courses for universities on storyboarding.

So now you can actually learn the profession and just go and apply. That really wasn’t the case before. Before, story artists were production illustrators, people who were there to sketch how the sets and props would look like, doing some character design, maybe some concept illustration. A director would need something and the illustrator on set would end up doing the storyboarding. This actually happened for me on a couple projects, as well, as I was transitioning into full-time storyboarding. So now it’s easier, just because there’s training and mentoring available. Now, a lot of directors of live-action and animation start as story artists and then move into directing. I mean, even Hitchcock, he started as a story artist. Jim Cameron was a story artist. A lot of top directors are.

Do different storyboard artists have different visual styles?

Well, some are looser, some are tighter, some are faster. When you’re working in production, particularly in TV, you’ve got to be incredibly fast. And you have to be more of a realistic style. Everything in animation also has to be storyboarded, so you can have a ‘cartoony’ style for that, but live-action directors don’t want to see a cartoony look. They want something that’s more realistic, you know, proportioned accurately. So that’s probably the biggest difference is cartoony versus realistic style.

How does a storyboard artist fit into the overall production workflow?

On The Walking Dead we have eight days of shooting to get an episode shot, which is not a whole lot these days. Eight days of shooting means eight days of prep, because we get a new director for every episode, plus two directors of photography (DP) and two first assistant directors (AD). One does evens, and the other does odd-numbered episodes. So one is prepping (while the other is shooting). When they’re done prepping with that director, they move with that director into production, and when they finish that they start prepping the next one. So that’s kind of the process. I’m working with a different director all the time.

Now, scripts are also constantly being worked on. So in that eight day prep they’re still working with the director and writers on the script. I won’t get a script until day three of eight. By day four or five the director and producer know which sequences need to be storyboarded. When we’re working on TV shows we don’t storyboard the entire thing. There’s no time. We storyboard stunts and effects, because those are the things that are the most up in the air. Or sometimes I’ll do special camera moves and special transitions, things that really need more intense planning.

On day four or five, I’ll sit with the director (often the DP will be there as well). We’ll go through those sequences, and I’ll sketch them out in real time in a video conference. We get off the call, I clean it up, put all the notes in, make it functional for production, and send it to the director for notes.

One of the things I do in addition to storyboarding that very few other live action story artists do is create an animatic in real time, and that’s a video storyboard. Because the software I use, Storyboard Pro, and the speed of working on my Wacom, I’m literally drawing on a timeline. So I’ll just quickly do a scratch track. And that helps me determine: Am I missing a shot? Is everything flowing? And the director gets to see if their vision is coming across the way they thought, because they can actually see it in video before they shoot the film. So it really, really helps the process.

Need to speed up your remote workflow?

Send large files, fast using MASV.

Who does a storyboard artist work with most on-set?

It’s the director, always, because it’s the director’s vision.

I like it when the DP is in meetings with us. On the first day the AD will come in at times, generally only on sequences, because they’ve got a lot to do in prep. But if they’re sequences then what I’m doing affects their schedule, and how they’re having to plan it, so they’ll step in for part of the meeting. Some producers, if it’s a really strong creative producer, will sit in. And, generally, that’s going to be it.

Now, sometimes I need to get photos from locations. I’ll talk to transportation if we’ve got special vehicles that are going to be there. Stunt coordinators will often come in and share video of how they’re doing the stunt or fight. Other times they’re building it from what I’m storyboarding. Sometimes it’s an effects person, but not often. They should probably be more involved, but again, we’re limited on time. And I’ll contact the art department to get their concept illustrations or 3D models.

What is your own, off-set workflow?

My actual workflow varies just a little bit, but the first thing I usually do is read the script for fun. I want to know the story. If I haven’t worked on the show before, I’ll look at whatever previous episodes I can. If it’s a movie I’ll try to watch something the director has done, so I can understand their visual style. I’ve done this long enough where I can pick out a lot of very specific traits of each director. And so I’ll start sketching that right away: I get right into their visual voice immediately.

Then I’ll read a script a second time and start paying attention to specific stunts and effects scenes. I’ll reach out to the AD and ask which sequences the director wants to do. When I’m working for someone else, I try not to put my vision out there before I start hearing the director’s vision. Because my goal is always to get their vision down, so when I see the finished piece, the finished footage looks exactly like what I illustrated. That’s success for me, and when I know I really did my job.

So then I start pulling references once I know the sequences. I’ll contact different crew heads or I’ll research myself, you know, what does this kind of tanker look like? Or what does that bomb look like? And I’ll pull reference materials. I’ll find out who the actors are, I’ll ask wardrobe what they’re wearing, and I’ll pull a bunch of headshots so I can reference them even as I’m sketching (it just makes it easier to determine who’s who, even in the rough sketches). And then I meet with a director (usually virtually) and we’ll go over all the shots. I’ll quickly make notes. I’ll send them my thumbnails immediately.

And then I go back and refine it with all the proper motion arrows, I’ll add motion to certain layers, I’ll add the camera moves, and I’ll make the art look cool. I’ll make the poses inspirational. And just so when you glance at it you understand the action better. Once it’s approved, every production is different on how they want me to get it to production. More and more are doing online databases where I can upload all the information. Sometimes there’s certain people I send it to. It varies.

What tools are required to be a storyboard artist?

Not everyone uses Storyboard Pro in live-action, but almost everyone does in animation. It’s a mix. A lot of people still use Photoshop, which I used to use, but it’s just not production friendly as far as how I can export things.

There are a number of softwares I’ve been using that have been speeding me up, that I integrate with Storyboard Pro. Things like ClipDrop, which is an amazing software where I can take a photo of a reference image, and it instantly drops out the background—I don’t have to touch anything. And it sends it from my phone to my desktop, I drag it right into Storyboard Pro and I can use it for reference drawing. It’s unbelievable how much time that has saved me.

I also use SketchUp a lot for 3D models. Most shows I’ve been working on use SketchUp for their sets. So when they send me a set, I’ll do that, but I can also bring that straight into Storyboard Pro and I can actually storyboard in 3D. There are some moves where the director wants to see very particular moves through a location, and I can actually do that all within Storyboard Pro and still keep drawing the characters in there at the same time.

You mentioned Wacom as part of your workflow. Which products do you use?

I have a lot of them. My main one on my desktop is the Cintiq Pro 24 Touch. And whenever I’m out on location, or if I’m traveling, I travel with my MobileStudio Pro. And instead of laptops, I have older Cintiq Companions. Some of my artists have the portable Wacom ones that they attach to their laptop. I also have the Wacom Express Key Remote.

Wacom Cintiq Pro 24 Touch

What types of files do you send?

I’m sending a PDF. Some productions have different ways they want to see everything: some are landscape, some are portrait. On commercials I’ll also send an export of individual JPEGs of each panel, because they like to do very specific setups for their clients when they’re doing their presentation before they shoot. And then I’ll send everyone an mp4 or movie file of the animatic.

Read More: Send Large Video Files with MASV

Does working remotely affect your workflow?

I’ve been doing remote for well over 10 years. I’m so comfortable with it. But I also look forward to being back on location, and on the set. I like the camaraderie of working that way. But I also really like walking around a set or location with the director to get a feel for it. It helps them plan everything out. So in the future, there will be less remote, but it will be more prominent overall.

We’d like to thank Mark for taking the time out of his day to educate us on the critical importance of storyboarding! It’s an absolute pleasure to learn more about the craft from an industry veteran such as Mark. This interview was possible by our partners at Wacom—the global leader in the pen display and tablet market for creative users.

We’re proud to announce that MASV and Wacom have partnered up to introduce an exclusive workflow offer for all new Wacom users. When you purchase any new Wacom Intuos Pro, not only do you get access to a suite of products from Adobe and Boris FX, you now also get a free 3-month trial and 250 GB of data credits to use with MASV file transfer.

Creativity shouldn’t have any limits. Although your ideas may know no bounds, inordinate file sizes can put a damper on any creative workflow. High-resolution video and photo files can result in large file sizes that are difficult to transfer to collaborators and clients. MASV is a large file transfer service built for creative professionals working remotely and on-location. MASV users can file packages of unlimited size on a high-performance cloud network that delivers files at max speed to our global network of 150 servers. In other words, MASV delivers massive files, to anywhere in the world, at blazing fast speeds.

This offer is available to all new Wacom Intuos Pro users once the product has been registered. Don’t use Wacom but are still in need of a large file transfer solution? Sign up here for a free trial of MASV.

Need to Send Large Files?

Create a free MASV account to get started