It’s crazy to think about how far we’ve come in the evolution of video editing when you see how easy it is to cut and rearrange footage on your mobile phone nowadays.

Video editors of today may be surprised to learn just how difficult video editing used to be—especially before the small miracle of non-linear editing (NLE) software.

Indeed, the initial iteration of video editing before editing machines or software—heck, before even scissors and tape—consisted of a cameraperson holding the shot until precisely the right moment. That was it. Even the rudimentary concept of cuts didn’t yet exist.

Fast forward to today, where machine learning and automation is replacing the more mundane (and sometimes painful) aspects of editing, like captioning and masking. The evolution of video editing has a rich history so let’s explore a timeline of highlights over the decades.

Your Search is Over. Share Files of Any Size Today.

Transfer large files for free with MASV.

The Dawn of Video Editing

Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein making edits with scissors. Image courtesy of Senses of Cinema.

All video editing during the industry’s nascent period was through a process known as linear editing, a destructive form of editing performed sequentially in the order of the final edit. While linear editing is still performed today, it has largely been replaced by non-linear video editing (more on this later).

- 1890: The Kinetograph, the first-ever motion picture camera, is developed by Thomas Edison and trusted assistant William Dickson. It films with celluloid at around 40 FPS.

- 1894: The Edison Vitascope, which includes a projector, debuts in the U.S. Film exhibitors begin arranging one-shot films into coherent programs using the technology, described as “a primitive form of editing”.

- 1900s: The first-ever cuts are made with scissors, tape, and editing tables (by the 1950s, tape will eventually be replaced with film cement). Because editors still can’t even view their films while editing, they’re forced to hold strips of film up to the light to make their cuts.

- 1916: The Technicolor color process makes its debut. By this time, film editors have begun experimenting with other color processes and rudimentary special effects.

- 1924: The Moviola—the first video editing machine—is introduced, allowing editors to, for the first time, make edits while simultaneously viewing their film.

- 1934: The Academy Awards present the first-ever Oscar for Best Film Editing (awarded to Conrad A. Nervig for the movie “Eskimo”). While not a technological or process advancement, the recognition raises the profile of film editing within the industry and for the general public.

- 1950s: Flatbed editing tables, such as the Steenbeck and Keller-Elektro-Mechanik (KEM), are introduced as an alternative to the Moviola. These tables feature a series of rollers and motorized plates. Film splicing machines, such as the Ciro Guillotine Tape Splicer, also make an appearance in the 1950s.

Source: Steenbeck Film Editing Machine from Wikipedia

The Emergence of Videotape

Everything changed with the invention of magnetic videotape, favoured by the TV industry thanks to its relative convenience and low cost, in the early 1950s. Videotape also provided other advantages over film; it uses the transverse scan method (which records on the full width of the tape), which allows more data to be stored on the same amount of physical tape, resulting in a lower required tape speed.

Read More: Media Preservation, Archiving, and the Historical Significance of Entertainment

- 1950s: Ampex Corp. unveils its Video Tape Recorder (VTR), the first machine to use magnetic tape to enable the recording and editing of video. The Ampex VRX 1000, which cost a princely sum of $50,000 USD at the time, is the first commercially successful videotape recorder and uses a 2″ Quadruplex format.

- 1961: The EECO 900 electronic editing controller becomes one of the first pieces of video editing equipment to utilize timecodes (a new feature of videotape at the time).

- 1963: Ampex EDITEC electronic editing is introduced, allowing the editing of video without physical cutting or splicing.

Enter Non-Linear Video Editing

The concept of non-linear editing—which allows video editors to change any part of a video, no matter if it’s at the beginning, middle, or end of the project—first appeared in the early 1970s. Unlike linear editing, non-linear editing helps prevent generation loss and doesn’t require the original film or video to be altered in any way.

- 1971: The CMX 600, also known as a RAVE (Random Access Video Editor), becomes the world’s first computer-powered NLE. It stores data digitally, costs around USD$250,000, and its disk drives are the size of domestic washing machines.

- Late 1980s/early 90s: The advent of digital NLE software such as Avid Media Composer and Adobe Premiere marks the beginning of modern video editing, transforming the editing suite from a studio address to anyone’s home or laptop computer. The first iteration of Avid supports resolutions of up to…640×480?

- 2000s: Improved processing power and multicore CPUs give personal computers the power to edit video using higher and higher resolutions, while new editing software such as DaVinci Resolve and Final Cut Pro provide even more options for video editors.

Fast, Easy, & Secure File Transfer for Video

Strengthen your media workflow security with MASV.

Present-day video editing

Today’s marketplace is dominated by non-linear video editing software combined with powerful digital cameras and technology-driven workflows. These tools have been further augmented by relatively new innovations such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) automation, cloud capabilities, and the ability to handle larger and larger files within the editing suite.

Offline vs. Online Editing

Non-linear editing since the early days was traditionally synonymous with “offline editing”, which requires editors to transcode lower-resolution copies of raw footage to serve as proxies during the editing process. That’s because these raw files were, in most cases, too large and cumbersome for contemporary tools to work with.

With the rise of more powerful NLE’s, however, offline editing has become less of a requirement. Applications such as Premiere Pro and Final Cut Pro X can now work with massive raw files, as long as your computer can keep up. Other software-as-a-service (SaaS) video editing tools allow for huge files by harnessing the virtually limitless computing power of the cloud.

AI/ML video editing tools

Because technology just keeps on rolling, some NLE’s now come outfitted with ML-driven automation for even more efficient video editing. The video review below from the Learn How to Edit Stuff YouTube channel shows how Runway ML uses machine learning to allow single-click masking and auto-rotoscoping with no cuts (as opposed to the typical tedious, frame-by-frame process). All rotoscoped footage can then be exported as chroma key colors, alpha channels, or video.

Reviewer Ian Sansavera says the software’s ML technology enabled him to rotoscope a clip in “1/24th the time” as with manual video editing software, though admittedly the latter offers more control choices such as feathering, contrast, shifting, motion blur, and decontaminating edges.

Read More: Why Ian Sansavera, from Team Liquid chose MASV above all other file transfer solutions

Other video editing software that take advantage of AI tools include:

- Kamua: A SaaS tool that uses computer vision algorithms to provide several automated tools, including AutoCut (AI-driven shot detection) and SmartCrop (AI-driven video crop).

- NAÏVE: Uses AI to analyze all your footage, remove low-quality clips, and automatically sequence the footage within Premiere Pro. It can also auto-sync audio and video.

- PluralEyes: Similar to NAÏVE, PluralEyes uses automation to quickly synchronize audio and video. It provides instant feedback through color-coded visuals on the NLE timeline as footage synchronizes.

- Descript: Auto-transcribes video into text, allowing you to edit video simply by cutting, tweaking, or rearranging the text in your transcription.

Mainstream video editing software has also gotten into the AI game recently. Final Cut Pro X offers ML-driven auto video cropping by analyzing clips for “dominant motion”. And Premiere Pro now offers several automated features including Color Match (instant color matching), Morph Cut (for more seamless transitions in interviews), Scene Edit Detection (automatically finds scene transitions and places the cuts), and Auto Reframe (removes the need for manual keyframe motion edits by automatically identifying the video’s focal point when reframing).

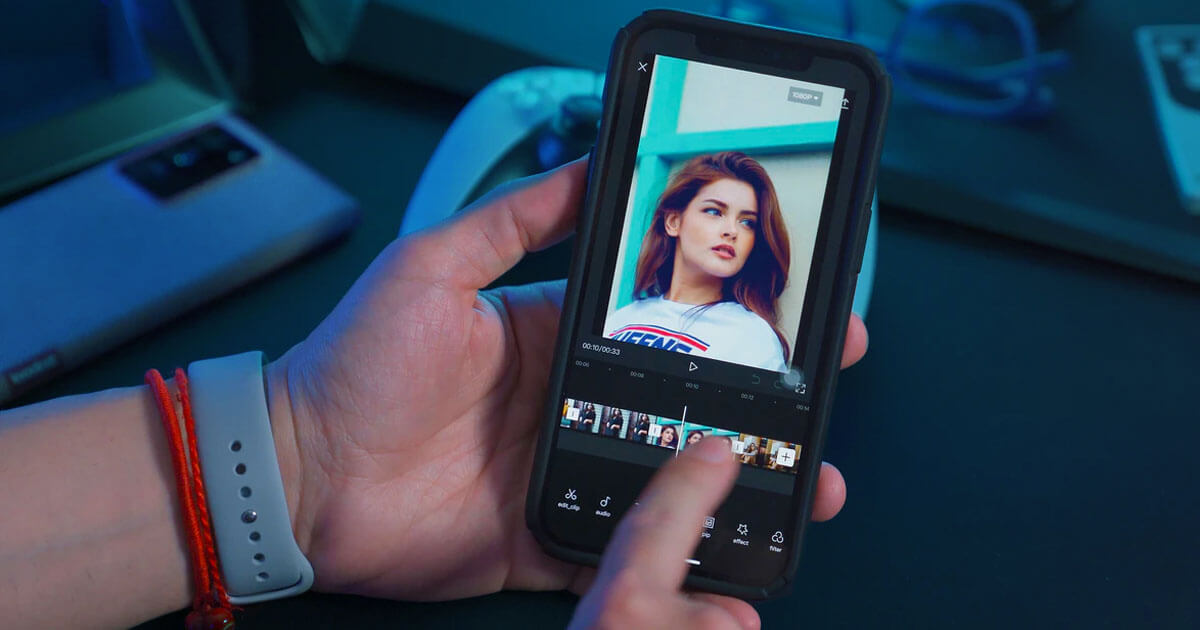

Mobile and the Further Democratization of Video Editing

The rise of mobile video editing apps just might be the greatest thing to happen to creators since YouTube. These apps make video editing a more lightweight, convenient experience available to anyone with a mobile device. It’s a whole lot easier to download an app than spend hundreds of thousands on editing equipment, after all.

Mobile video editing apps are also typically far easier to use, with much a lower barrier to entry, than full editing suites.

We’ve already taken a spin through some of the best free mobile video editing apps. But there are other options out there, including:

Adobe Premiere Rush: Made for social media creators whipping up content on the fly, Premiere Rush automatically converts videos to fit the required specifications for various social media channels. Users can tailor transitions, customize titles, apply color correction, add audio, and adjust video speed, among other capabilities.

LumaFusion: Marketed more to mobile journalists, filmmakers, and pro video producers, LumaFusion offers multitrack video editing on the go (featuring six video/audio tracks and six additional audio tracks).

Quik: The official GoPro app allows users to remotely control a GoPro camera from their mobile device, along with simple yet powerful editing tools such as auto-sync video and music, video speed changes, trimming, and color correction.

Your Search is Over. Share Files of Any Size Today.

Transfer large files for free with MASV.

Edit with NLE’s. Transfer with MASV.

Modern NLE’s allow video editing of raw files in 4K or even higher resolutions. That’s amazing for filmmakers and creators—but that’s only part of the editing story. When you need to share large video files with collaborators and clients, you need a fast, reliable file transfer solution.

MASV is a digital media file transfer tool that allows filmmakers, creators, and other video professionals to quickly and securely share video content with anyone, anywhere. Other file transfer solutions will impose data caps or choke transfer speeds but MASV has no file size limits. There’s no need to chop up or compress raw video files before sharing. And those large video files ride on a dedicated network of 150 global servers at max speed.

Best of all, MASV is an enterprise-grade secure file transfer solution. Transfers are backed by the Trusted Partner Network; a security initiative spearheaded by the Motion Picture Association and the foremost authority in content protection for media & entertainment.

In the middle of a big editing project and need to transfer a large file asap? No sweat—just sign up and get free data transfer for free every month.

Fast, Easy, & Secure File Transfer for Video

Strengthen your media workflow security with MASV.